Humanities 2 addresses the professions of architecture and urban design and how it can have an impact beyond the bounds of its own sites; architecture in the city can have unexpected political, economic, environmental, and other implications, questioning the ethics of architectural and urban practice.

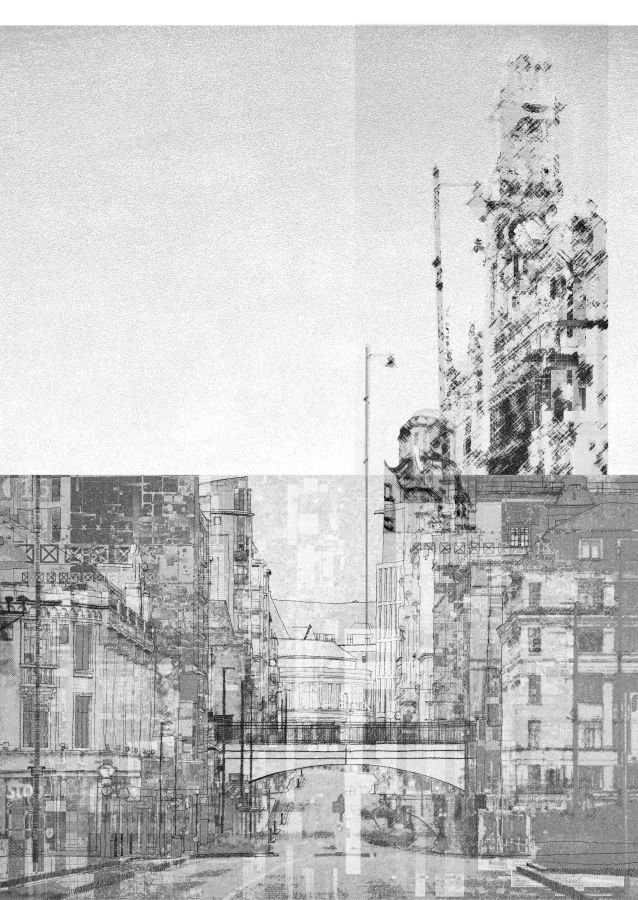

With Tracing the City, we turn our focus towards a critical approach to architecture and the city, looking at processes of production, consumption and maintenance that constitute the built environment and beyond. We do this by questioning common definitions of a static city by acknowledging that it is alive and constantly evolving through and with the mechanisms that make up its networks. Our explorations are accompanied by new methods of tracing (mapping) these city relations in creative, non-linear ways. We look at a wide range of urban artefacts and discover new methods of understanding their multiplicity. The course is structured with a dual component in mind: a) it explores historical and theoretical underpinnings of urban practice by addressing notions of nature, technology, race, and class as embedded within particular socio-political contexts, and b) it suggests alternative methods for mapping these relations by zooming in and carefully unpacking their complexity.

Sustainable Urban Futures is a central pillar of our broader strategy on creating climate literate landscape architecture graduates. The module encourages students to develop their critical thinking on a range of issues relating to climate breakdown and biodiversity loss. Students cover debates including the role of technological change vis-à-vis human behaviour, the interconnectedness of humans with other species, insights from indigenous knowledge, and how to advocate on behalf of the climate. We welcomed guest lecturer Professor Luca Csepely-Knorr (University of Liverpool) who discussed ‘Context, precedent, antithesis: the role of nature in architecture’. The course draws on literature from a variety of disciplines to help students understand the importance of developing a theoretically informed positions when addressing the climate emergency. Central to the course is an appreciation of the complex social, environmental, and economic contexts within which the built environment disciplines operate, and how this translates into an ethical and moral responsibility towards engaging with the climate emergency.